Meet your mitochondria, Part 1

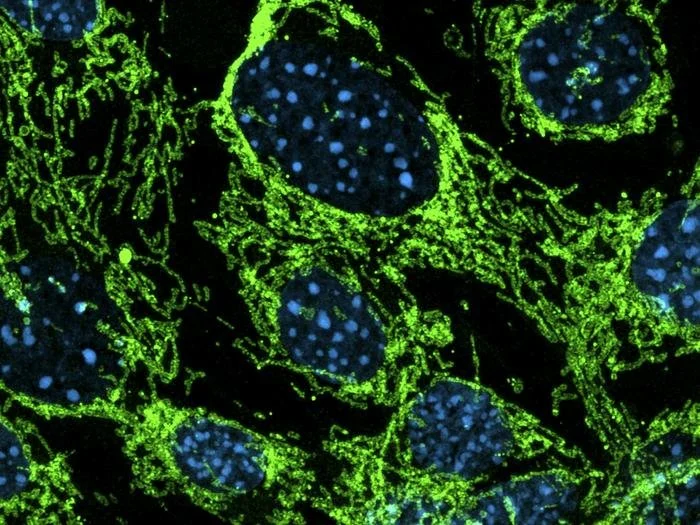

Not inert blobs or little factories… active, coordinated, mobile networks of healthy mitochondria (green) managing the processes of life. Image credit: MPI of Immunobiology & Epigenetics, Freiburg from eurekalert.org

Back in high school, they told you a mitochondrion was “the power house of the cell.” In fact, if you google “mitochondria” that’s still what appears. So it might surprise you to hear that’s an outdated—and in fact an incorrect and just plain pathetic—definition. They are still illustrated as portly little ovals drifting at random within a cell. Sure, this might be what they look like after they die. But in life they are dynamic, mobile, lithe and cooperative shape-changers, and they are running the show. This post is the first in a series taking a closer look at the astonishing life of your mitochondria, and how they make you what you are.

Who are your mitochondria? I put the question that way because they are indeed very small someones. They are not so much organelles (“specialized structures within cells”) as they are members of a vast, extraordinarily organized network which lives a semi-autonomous life within you. The more deeply researchers examine this network, the more clear it becomes that the state of your mitochondria determines whether you are healthy or sick. They are inextricably involved in metabolism, fertility, vision, sleep, mood, and so much more.

Just as we’ve been told the mitochondria are little blobs that “make ATP,” we’ve been told that the nucleus of a cell, in particular the genetic material contained in the nucleus, is the “brain,” making decisions and issuing commands. It’s just simply not so. By now most of us have heard that genes can be turned on or turned off, activated or not. Your genes contain many, many potential versions of You. But who governs the expression or nonexpression of particular genes? The living network of mitochondria.

They aren’t just doing a couple of important jobs around the cell. They are so much more fundamentally who we are, and at the same time they retain the capability of operating independently. They are perceiving, processing information, making choices on behalf of a world vastly larger than themselves, honoring consensus, communicating over great distances, creating chemical tools to solve problems, enacting emergency measures when things go wrong… Perhaps it sounds like science fiction, but it’s the tip of the emerging iceberg of our comprehension of what these tiny beings are and what they’re doing. And by extension, a new understanding—or at least a new crop of vital questions—is emerging about what a human being is.

Now to backtrack about… oh, about one and a half billion years, and properly begin this story. That will help to clarify the semi-independent nature of our mitochondria, and also their ability to network, exchange information, manipulate genetic material, and also some of their frightening behaviors when chronically overstressed or damaged.

Once upon a time, in the days when only single-celled organisms resided on Earth, a bacterium (or bacterium-like organism) became incorporated into a larger organism. We’ll never know how they worked it out, but the merger allowed a symbiotic relationship to begin which became stronger and stronger over time. By the time organisms eventually became more complicated, with many cells and new capacities, the tiny resident beings had developed their own societies with their hosts. And it fact they had become indispensable “organelles.” A branch of larger, multi-cellular organisms became plants; within their cells, these adaptive organelles specialized in processing sunlight: the chloroplasts. Another branch became animals, and the organelles, called by us mitochondria, gradually took on the central role they still play today.

In Part Two we’ll look more closely at some of those vital functions. We’ll also consider how we can support the health of this essential organ within us, which I’ll call mitochondrial society. And we’ll look at some examples of what happens when we inadvertently harm it.