Meet your mitochondria, Part 2

The cristae within each mitochondrion adjust their shape to communicate with their neighbors and manage the cellular processes.

One of the world’s top researchers of mitochondria—he has effectively redefined mitochondrial biology—is Martin Picard, working at Colombia University. He suggests that these organelles should be seen as “the information processors of the cell. . . They are equipped with a surprisingly wide variety of receptors to sense what’s going on in the cell, they integrate all this information, and they then tell the nucleus and other organelles what to do to maintain the health of the organism.” This subtly turns a primary paradigm of modern biology on its head: the doctrine—now dogma—that the nucleus of a cell is the “brain,” and the origin of all changes of the chemistry and behavior of the cell. (Other areas of research are currently overturning that dogma as well; more on that one day soon.) It appears that the nucleus, as the repository of the genetic material, is more like a library, toolshed, and laboratory. None of those worthy resources is much use without someone to make use of them. Who might that someone be?

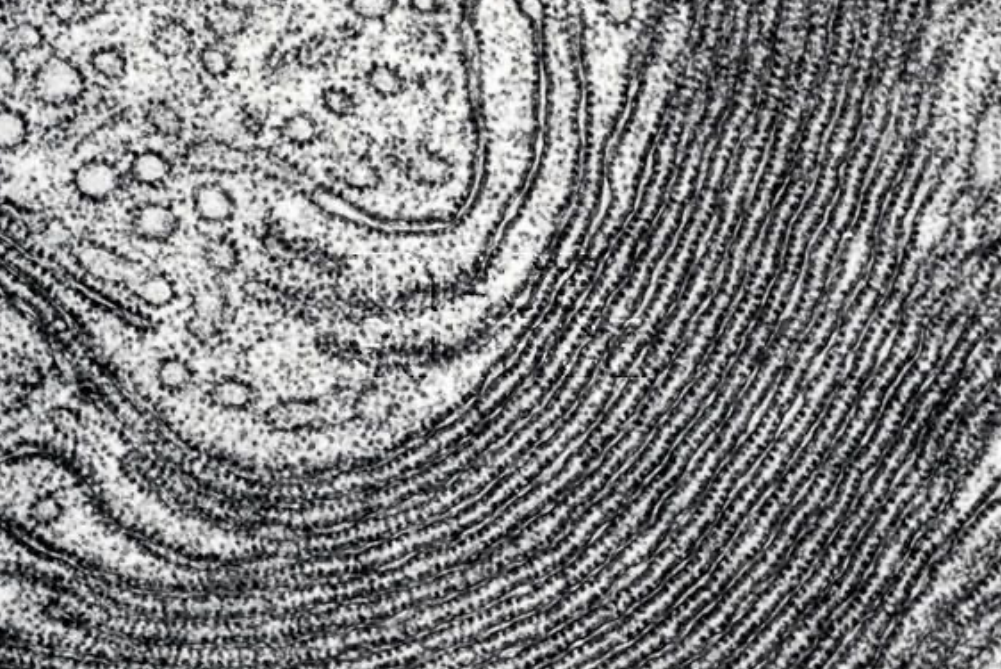

Soon after earning his PhD from McGill University in Montreal, Picard made a startling observation. Within each mitochondrion, the inner membrane has a large surface area, accomplished by folding into shapes called cristae. What he noticed was that not only did the cristae change shape, they did so in such a way that they aligned with the cristae of other cells. Were they somehow communicating, he wondered? Cooperating? Being “social?” After many years of work (and some very prestigious awards) Picard, along with a whole tribe of other researchers in this new field, confidently say Yes. And the implications of this are enormous. In fact after some years of following and pondering these findings, I feel it goes so far as to change and expand the meaning of the word social.

Another researcher, Tim Shutt, coined the term CEO (“Chief Executive Organelle”) for the mitochondria, since as well as being energy generators they receive information, analyze it, select a response designed to best support the health and efficiency of the cell, and instigate that response, choosing also the best mode of communication—electrical, chemical, even quantum means. We learned in biology classes that hormones are messenger molecules; how interesting, then, to learn that some of the most important ones are synthesized in mitochondria. “Information” they receive includes nutrients from food, as well as other molecules (one of the most important being oxygen), temperature, light… seemingly, virtually any kind of input that could impact the health of the host organism. I say host because, as mentioned in Part One, to a large extent they retain their independent nature while living within the cells and bodies of humans and other animals. The most striking thing to note is that they choose a reaction which benefits the larger organism, not themselves as organelles, the cell they reside in, or even their local neighbors. For instance, if mitochondria are in a damaged or diseased cell, they may decide the “right” thing to do is sacrifice the cell. In other words, they can trigger apoptosis, the build-in self-destruct capacity of ageing or dysfunctional cells to keep the population healthy (failure of this mechanism is a notable feature of cancer).

The information processing is, according to the newest research, organism-wide. These little beings are networking so extensively, they are apparently key drivers of adaptation, epigenetic change, ageing, healing… They network by creating “cross-talk” between fellow mitochondria even across cell boundaries, but they also leave their cells and travel in the bloodstream to other locations in the body. Ponder this. An organism-wide network of mobile, profoundly organized little beings which determine our state of health or disease.

Impaired or misshapen mitochondria, or insufficient numbers of them, are associated with all kinds of diseases. Picard’s work is applied to (among other things) psychiatric health. The unfortunate reality of the wholesale decline in human health and the rise of degenerative and immune-related diseases are largely traceable to mitochondrial problems—from cancer and heart disease to dementia and infertility. The health crisis is, tellingly, most strongly manifest in wealthy, developed nations and demands that we examine the diet and habits that are creating it. Carbohydrate-heavy processed foods, toxic fats (including canola, soy, and other vegetable oils we have been told are “healthy”), inactivity, disrupted circadian rhythms, and many other “new normal” lifestyle factors are implicated. I would suggest that dozens of unfamiliar synthetic chemicals, in the form of medications, are playing a critical role, as well as the chemicals of industrial agriculture, modern building materials, the bizarre molecular cocktails of personal care products, vehicle emissions… The truth that emerges here is that although pharmaceutical companies will try very hard to convince us otherwise, there really is no short cut to restoring our mitochondrial health. And unless we do so, we will continue to spin our wheels in pursuit of wellness, all the while sliding helplessly downhill.

But in closing I want to offer a deeper idea. Mitochondria transform energy; they turn the energy contained in molecules of food, for instance, into forms useful for the body. Energy, and the flow of energy, is the basis of life (and health). But consider the fact that this is true for the mind as well as the body. As the receivers and transformers of (as far as we can tell) every type of input—from food to oxygen to sense impressions—the realization is dawning that this companion network within us is the source of consciousness. Your individual experience of the life is formed by the interaction of your mitochondrial network with the world, both within and around you.